The Gobbo: A Lucky “Hunchback”

Exploring the Spiritual Significance of Physical Differences

First and foremost, it’s important to address the terminology. Referring to an individual as a “hunchback” is not considered polite. The medical term for this condition is kyphosis, and The House of Good Fortune presents this discussion purely as an exploration of cultural beliefs and practices—not as an endorsement.

Throughout history, physical differences such as kyphosis, dwarfism, spinal curvature, or crossed eyes have often been viewed through a lens of mysticism. Many ancient societies believed these traits endowed individuals with supernatural abilities or the power to attract good fortune and ward off misfortune. Far from being marginalized, those with these differences were often revered and integrated into important social and spiritual roles.

Sacred Roles Across Cultures

In Mesoamerica, individuals with hunched backs held positions of honor. Within the Aztec royal court, they were believed to possess unique spiritual attributes and were entrusted with special duties. These traits are also celebrated in Olmec art, where depictions of individuals with kyphosis highlight their significance in rituals and mythologies.

In Yoruba culture, physical differences such as kyphosis, dwarfism, and albinism are seen as marks of divine intervention. These individuals are believed to be touched by Obatala, the god who shapes the human form in the womb. As a result, they are viewed as sacred beings, capable of bestowing blessings, wealth, and good fortune upon those who encounter them.

The Myth of Obatala and the Gift of Fortune

One Yoruba myth beautifully illustrates the reverence for individuals with kyphosis. According to the story, Obatala once commanded a hunchback’s back to open, filling it with treasures beyond imagination—glistening gold, precious gems, and untold wealth. He then sealed the back, creating a living vessel of abundance. When a deserving man encountered this individual and gently rubbed their hump, the treasures within were revealed, bestowing prosperity upon him.

This tale reflects a deep cultural respect for physical differences, portraying them not as imperfections, but as conduits for divine generosity and wonder.

The Gobbo and the Power of Peculiarity: A Fascinating Legacy of Luck

In ancient Rome and Greece, the belief in the mystical power of physical differences was widespread. Among these, the “hump” of an individual with kyphosis was thought to bring good luck when touched. These individuals were also believed to have the unique ability to deflect the evil eye (malocchio), a malevolent force feared for its power to bring misfortune.

Why the Gobbo Was Thought to Protect

The logic behind these beliefs lay in the gobbo’s striking appearance. According to tradition, their unusual features would capture attention, eliciting laughter or curiosity. This shift in focus was said to redirect the evil eye away from its intended victim, neutralizing its harmful effects. In this way, the gobbo became both a protector and a living emblem of good fortune.

The Gobbo in Art and Culture

The enduring mystique of the gobbo inspired artists and artisans across centuries. In the early 17th century, French artist Jacques Callot (1592–1635) created a series of 20 etchings known as “Grotesques,” which depicted dwarves and other characters with physical differences. These etchings captured the imagination of audiences and influenced the design of porcelain figures crafted by Villeroy, featuring dwarves and hunchbacks adorned with whimsical and lucky motifs.

The Gobbo in Italian Tradition

The Italian word for “hunchback” is gobbo. In Italy, the gobbo evolved into a richly symbolic figure, who is often depicted as a dapper gentleman in a coat and top hat, both adorned with lucky amulets. Also known as O’Scartellato, this charming character is typically portrayed holding a horseshoe in one hand while making the cornuto sign (a protective hand gesture) with the other.

The gobbo’s ensemble is often embellished with garlic bulbs and other portafortuna (good luck charms), cementing his role as a protector against misfortune. In some depictions, he is rendered as a mythical hybrid—half man, half horn—known as the corno gobbo.

Gobbo Charms and Modern Legacy

Charms and amulets depicting the gobbo were historically crafted from coral, mother-of-pearl, or silver. These were worn as bracelets, necklaces, and watch chains, serving as talismans for those seeking fortune and protection. Today, like so many things, these charms are often made of plastic, but their significance endures. The gobbo remains a fixture of Italian-American festivals, such as the Feast of San Gennaro in New York City. Visitors might encounter gobbo amulets, t-shirts bearing his likeness, or even a corno gobbo keychain, blending age-old tradition with modern whimsy.

The belief that hunchbacks are “lucky” is by no means limited to the distant past. A casino in Monte Carlo employed a “hunchbacked” man because of the belief that having a “hunchback” cross your path was a lucky omen. Whenever a successful gambler was about the leave the table, the management would queue “Mr. Hunchback” to walk past the table in the hope of enticing the gambler to stay and press his luck (See Superstition and Folklore by Michael Williams). And in early 20th century America, sports teams employed “hunchbacks” (and dwarves) as lucky mascots. In Philadelphia, for example, both the Phillies and Athletics employed hunchbacked youngsters as batboy mascots.

And of course, there is perhaps the most famous hunchback of all time, Quasimodo, or The Hunchback of Notre Dame, whose life was, tragically, devoid of good fortune.

A Symbol of Strength and Luck

The gobbo is far more than a historical curiosity. He embodies the resilience and resourcefulness of those who turn adversity into strength, transforming physical differences into powerful symbols of protection and good fortune. In the gobbo’s enduring legacy, we find a reminder of the power of individuality and the timeless allure of the extraordinary.

Further Reading: A digression into the “other” meaning of Cornuto: Il Magnifico Cornuto

A postcard a lucky charm which is illustrated by a hunchback. Chromolithograph. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Hunchback Charm, Italy. Pitt Rivers Museum Collection.

Villeroy Hunchback c. 1750. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Three Coral Gobetti, House of Good Fortune Collection.

Hunchback Figure, Villeroy. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Hunchback with a Cane, Jacques Callot. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hunchbacked Figure. 12th–9th century B.C. Olmec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Link

Spanish Kid Gloves with Figures by Jacques Callot. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Man Scraping A Grill in the Guise of a Violin, Jacques Callot. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Cast metal charm depicting a hunchback, Il Gobbo, from the Horniman Museum & Gardens

An example of Scartellato with cornicello

Cast metal charm depicting a hunchback, Il Gobbo, from the Horniman Museum & Gardens

Seated Hunchback

Advertisement for O'Scartellato Apartments

Gobbo Portafortuna

Hunchback Leaning on a Staff, from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cast metal gobbo (as found), House of Good Fortune Collection

Gobbo figurine with gilt cap, slippers and roasted chicken; House of Good Fortune Collection.

So what are we to make of this “Gobbo”?

The Gobbo pictured below looks a lot like Billiken, no? For those astute readers who are already aware of Billiken, please proceed. But for those who need to come up to speed, this essay by Dorothy Jean Ray should help. (You can also read about Billiken here.)

Let’s try to unpack this…

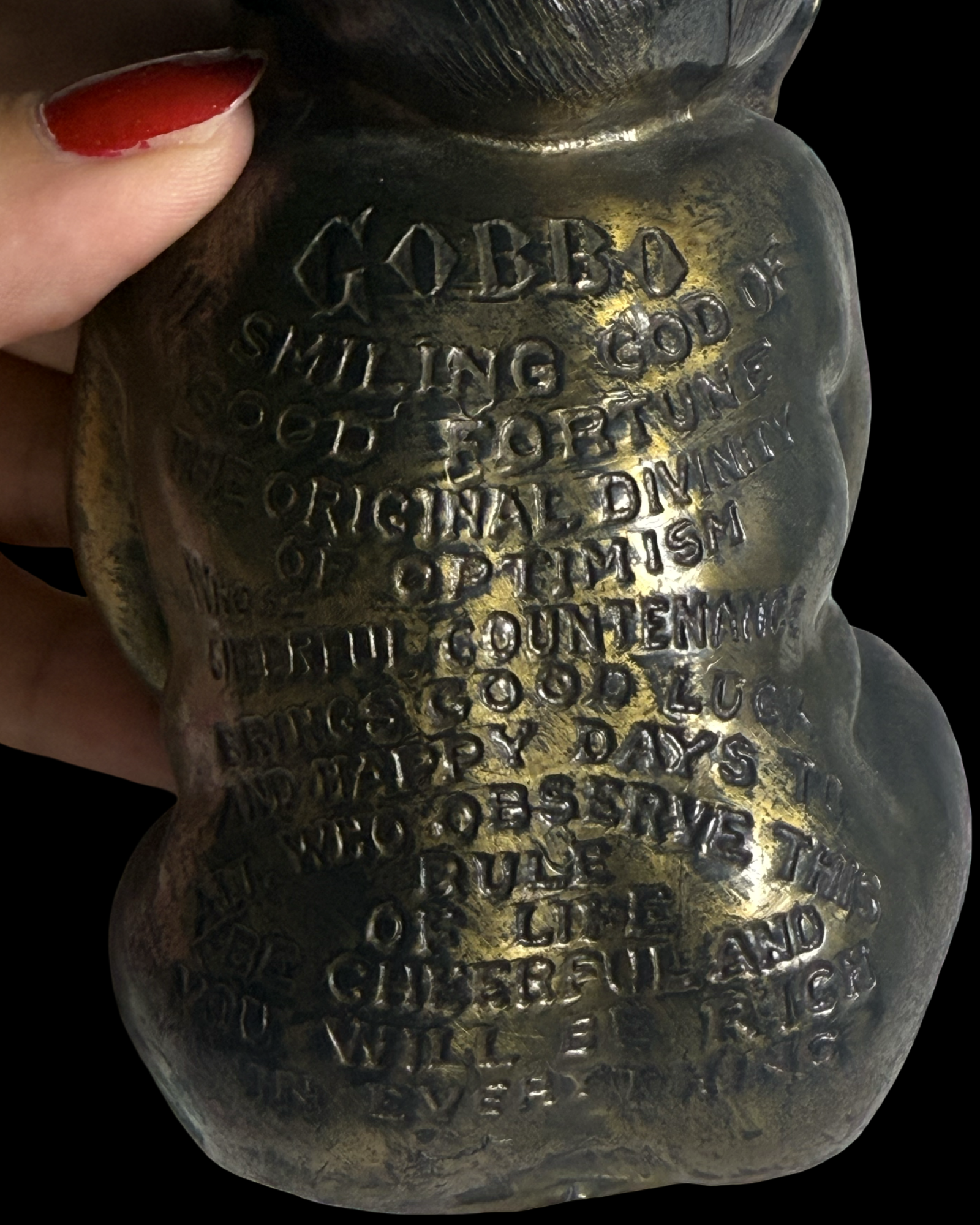

Here we have a cast metal figure from 1909 that reads: “Gobbo: Smiling God of Good Fortune, Original Divinity of Optimism Whose Cheerful Countenance Brings Good Luck And Happy Days to All Who Observe This Rule: Be Cheerful and You Will Be Rich in Everything”

What are we to make of this, dear readers? Have Gobbo and Billiken merged into a single, smiling hybrid? This figure’s features are decidedly less Billiken-ish, and there is no discernible “hump” as one would expect from a Gobbo.

It seems that Billiken’s passing resemblance to other figures like Kewpies and Gobbos led to some convergence among popular mascots at that time. So here we have a “radiator cap” or “bank” that has combined Gobbo’s name’s with Billiken’s positive outlook. It also echoes the Yoruba myth’s promise of wealth.

The fusion may be accidental, or it may be intentional—a marketing invention dressed in the robes of folklore. Still, the message is unmistakable and oddly timeless: Be cheerful, and you will be rich in everything.