Is the Whirling Log the same as the Swastika?

The House of Good Fortune must be honest with you, dear readers: this one is complicated. The symbol in question — a four-armed figure known today by many as the swastika — carries centuries of meaning, both luminous and dark. But long before it was misappropriated in the 20th century, this ancient design appeared across the world as a sacred sign of good luck, movement, balance, and the life-giving power of the sun.

Known variously as the manji in Japan, fylfot in Europe, gammadion in Greece, and swastika from the Sanskrit for “well-being,” this symbol has been revered by Native American, Indian, Tibetan, Greek, and other cultures for millennia. Often found on jewelry, textiles, pottery, buildings, and sacred objects, it was understood to represent the four cardinal directions, the turning of the seasons, and the eternal cycle of life.

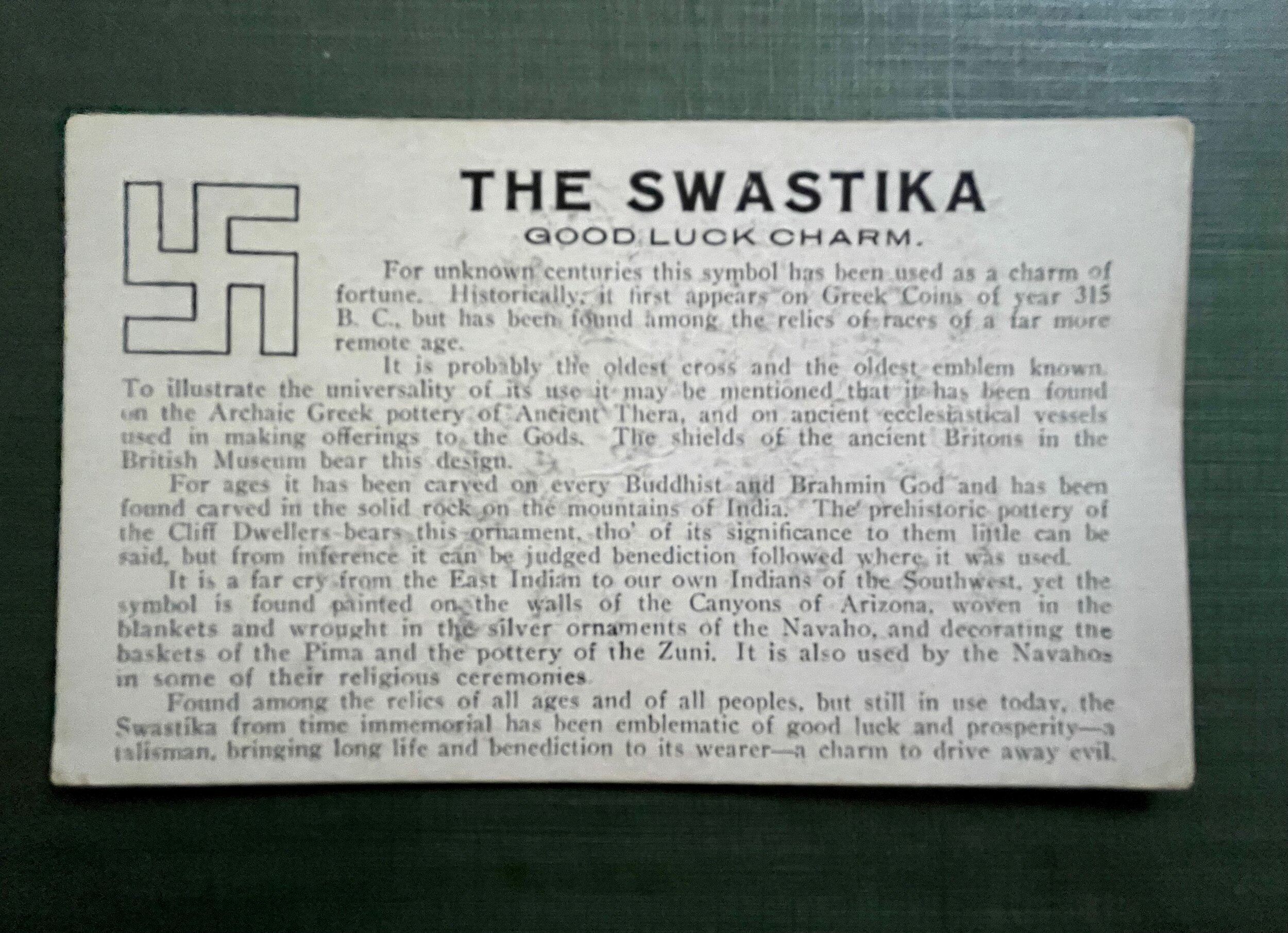

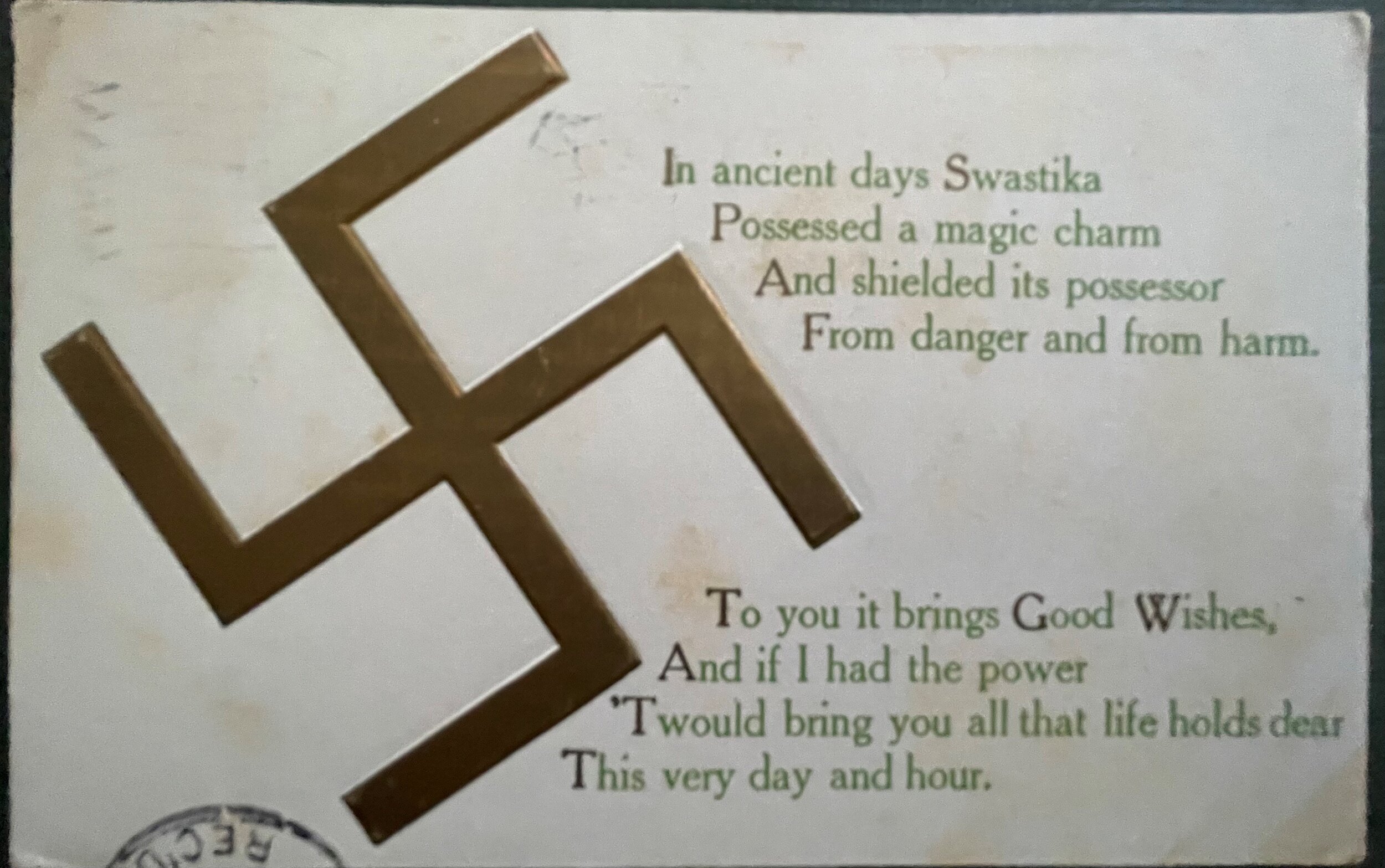

As one undated postcard from the Fred Harvey era in New Mexico explained, “The Swastika from time immemorial has been emblematic of good luck and prosperity — a talisman, bringing long life and benediction to its wearer — a charm to drive away evil.”

In the modern era, most people recognize the swastika as a symbol of the Third Reich and the terror of the Holocaust. But why should an ancient and universal symbol of good fortune that has been used for thousands of years be ceded to neo-Nazis? If the Nazis lost the war, why do they get to keep the swastika? Is there no way to reclaim the symbol and restore its original meaning?

The House is hardly the first to raise this question; in fact, it has been debated at length. The House directs you to an article in Quartz, Can the Swastika Ever Reclaim its Original Meaning?, which juxtaposes the positions of two men who have devoted thousands of hours to pondering this very question. One is a Jewish historian; the other is a Buddhist priest. Each has written a book on this subject. It’s a fascinating article that is worthy of contemplation. The House recommends.

For those who need a summary, the gist is as follows:

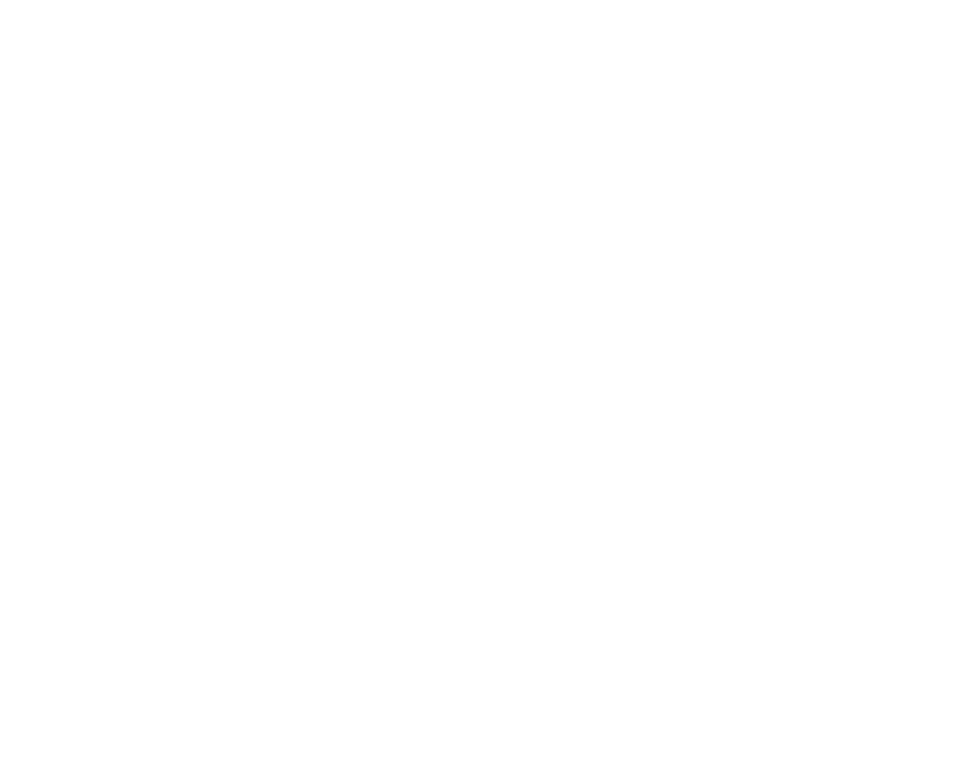

Pro-reclamation: The swastika has been associated with positive attributes like peace, good fortune and good health for thousands of years; Not only ere the Nazis late to the party; they used a hakenkreuz, not a swastika, and Hitler never used the term swastika. Linguistic accuracy is important because words have meanings and one symbol is not the other. The Buddhist manji is and always has been a symbol of peace, and awareness of that fact is important because truth should trump cultural taboos, particularly erroneous ones.

Anti-reclamation: Reclamation is not possible — at least in the West — so long as the symbol is used by neo-Nazi extremist groups. Who cares if it was rotated, mirrored or whatever - the Nazi symbol has contaminated any symbol that even vaguely resembles a swastika. Arguments about whether Hitler used an actual swastika or even the term swastika are semantic at this point. There is no serious way to distinguish the symbols at the top of the page. The swastika is forever ruined and should not be rehabilitated.

So where do we go from here?

The House is reminded of The Appropriation of Cultures, a short story by Percival Everett. The main character is a young Black man named Daniel. One night, as he is playing guitar with a band in a bar near the University of South Carolina, some drunk frat boys ask him to play Dixie. There is tension in the room as the other patrons understand the power dynamics of this request. Daniel pauses and instead of storming off or starting a fight, he gives a stirring, soulful rendition of Dixie that leaves the crowd astounded. Daniel goes home and reflects on what happened that night in the bar. I’ll fast forward, dear readers, in the interest of brevity, but basically Daniel considers his own complicated relationship to his southern identity and comes to claim the rebel flag as his own. He buys an old pick-up truck with a Confederate flag decal in the window and starts to drive it around town.

The story concludes: “Soon, there were several, then many cars and trucks in Columbia, South Carolina, sporting Confederate flags and being driven by black people. Black businessmen and ministers wore rebel flag buttons on the their lapels and clips on their ties. The marching band of South Carolina State College, a predominantly black land grant institution in Orangeburg, paraded with the flag during homecoming. Black people all over the state flew the Confederate flag. The symbol began to disappear from the fronts of big rigs and the back windows of jacked-up four-wheelers. And after the emblem was used to dress the yards and mark picnic sites of black family reunions the following Fourth of July, the piece of cloth was quietly dismissed from its station with the U.S. and state flags atop the State Capitol. There was no ceremony, no notice. One day, it was not there.”

Is it a fantasy that something similar could happen to the swastika? Probably. It would take a staggering amount of individual and collective courage, but would extinguishing a symbol of hate be worth it? After all, it is not without precedent. The pink triangle, another bit of Nazi symbolism, was appropriated by gay men during the AIDS crisis in the 1990s and has become a symbol of LGBTQ pride.

Before his death in 2012, Canadian artist and mystic Man Woman spent much of his life on a personal and deeply spiritual quest to restore the swastika to its original, life-affirming meaning. His book, Gentle Swastika, features a dove-filled swastika on the cover. Through his art, tattoos, and travels, Man Woman gently but persistently urged the world to see past the shadows of history and remember the swastika as it once was — a holy sign of peace, prosperity, and cosmic order.

So what about the whirling log?

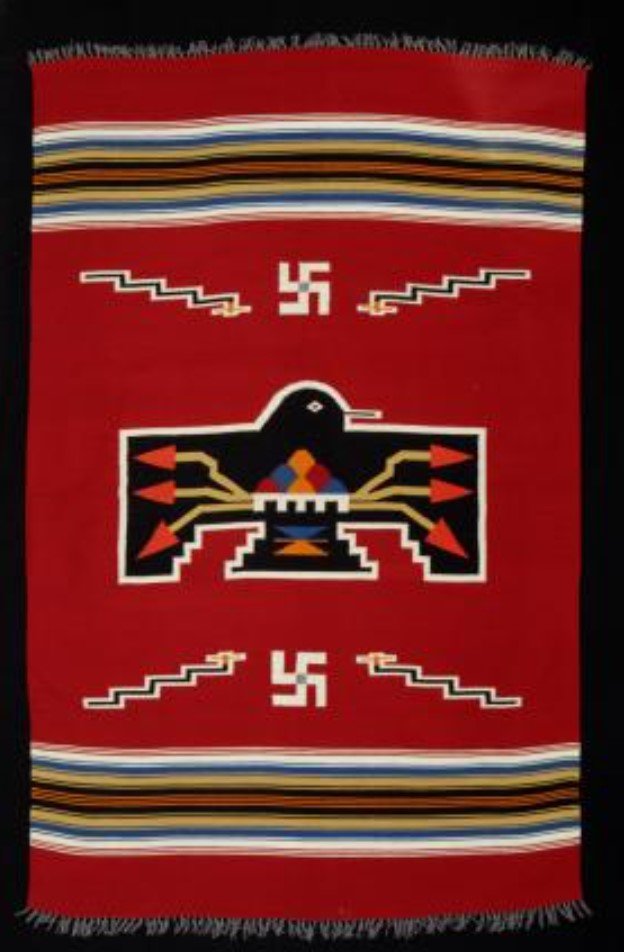

The whirling log is a symbol used by the Navajo, or Diné, people. It represents “that which revolves.” First used in sand paintings and healing rituals, the whirling log later became a popular motif in textiles such as rugs. There are examples of whirling logs that revolve clockwise, like the Hindu swastika, and counter-clockwise like the Buddhist manji. Sometimes the same piece will depict the symbol in both orientations.

According to a grossly abbreviated version of a Native American legend, the origin story of the whirling log involves a young man who sets out on a quest for healing and knowledge. He enters the river on a hollow-out log and is carried through various trials, encountering holy beings who teach him songs, rituals, and powerful medicine. When he returns, he brings this sacred knowledge back to his people.

The whirling log thus symbolizes movement, balance, and the sacred journey toward harmony between the world and oneself.

Whirling log pattern woven into textile

As you can imagine, the use of the swastika as decoration became a little…uh, fraught… during wartime, and four Indian tribes, at the urging of the U.S. government, formally renounced the swastika and vowed not to use it in their designs anymore. While it appears that the Native Americans who made this public statement took the position that the whirling log and the swastika were indistinguishable, public opinion seemed to be somewhat mixed at the time. On February 26, 1940, The Los Angeles Times reported this move as “Indians Bar Swastika Design as Protest Against Nazis” while the Twin Falls News declared, “Arizona Indians Bow to Hitler”: “Chalk up another victory for the Nazis, this time on American soil. Four Arizona Indian tribes have capitulated to Hitler, bowed the knee, and given up their ancient symbol, the swastika, because as their resolution states, the Nazis have desecrated it.”

Eighty years later, and the debate is still more or less in the same place.

The House will end this post with a quote from the author of the Quartz article, who moderated the discussion on reclamation of the swastika: “It made me believe in the power of civil discourse to open us to new worlds, so that we might develop appreciation, if not outright acceptance, of other points of view.”

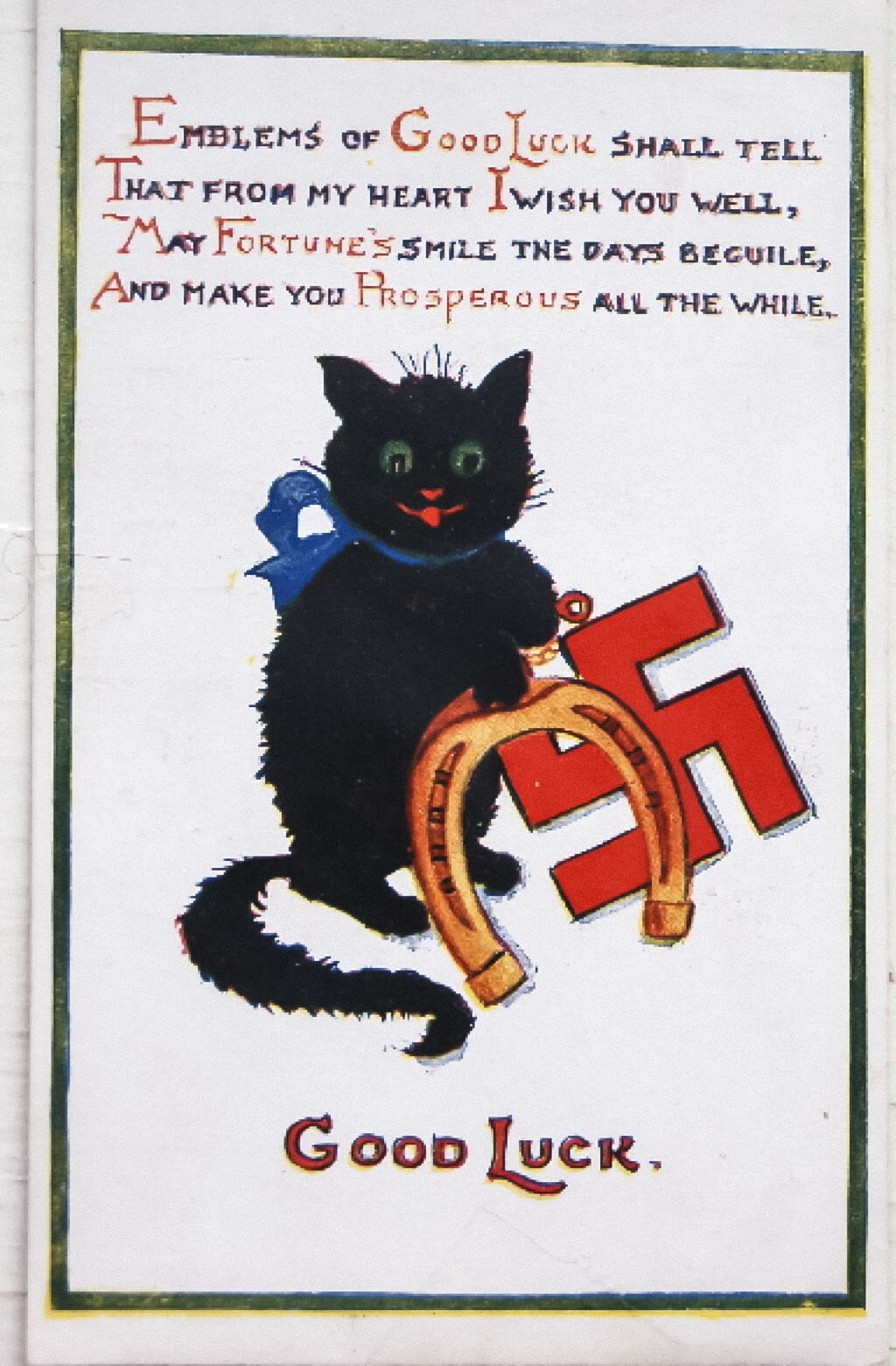

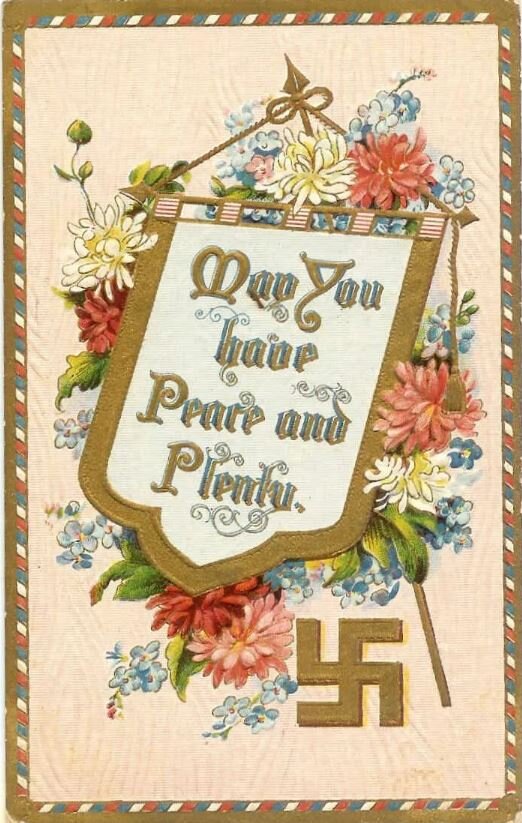

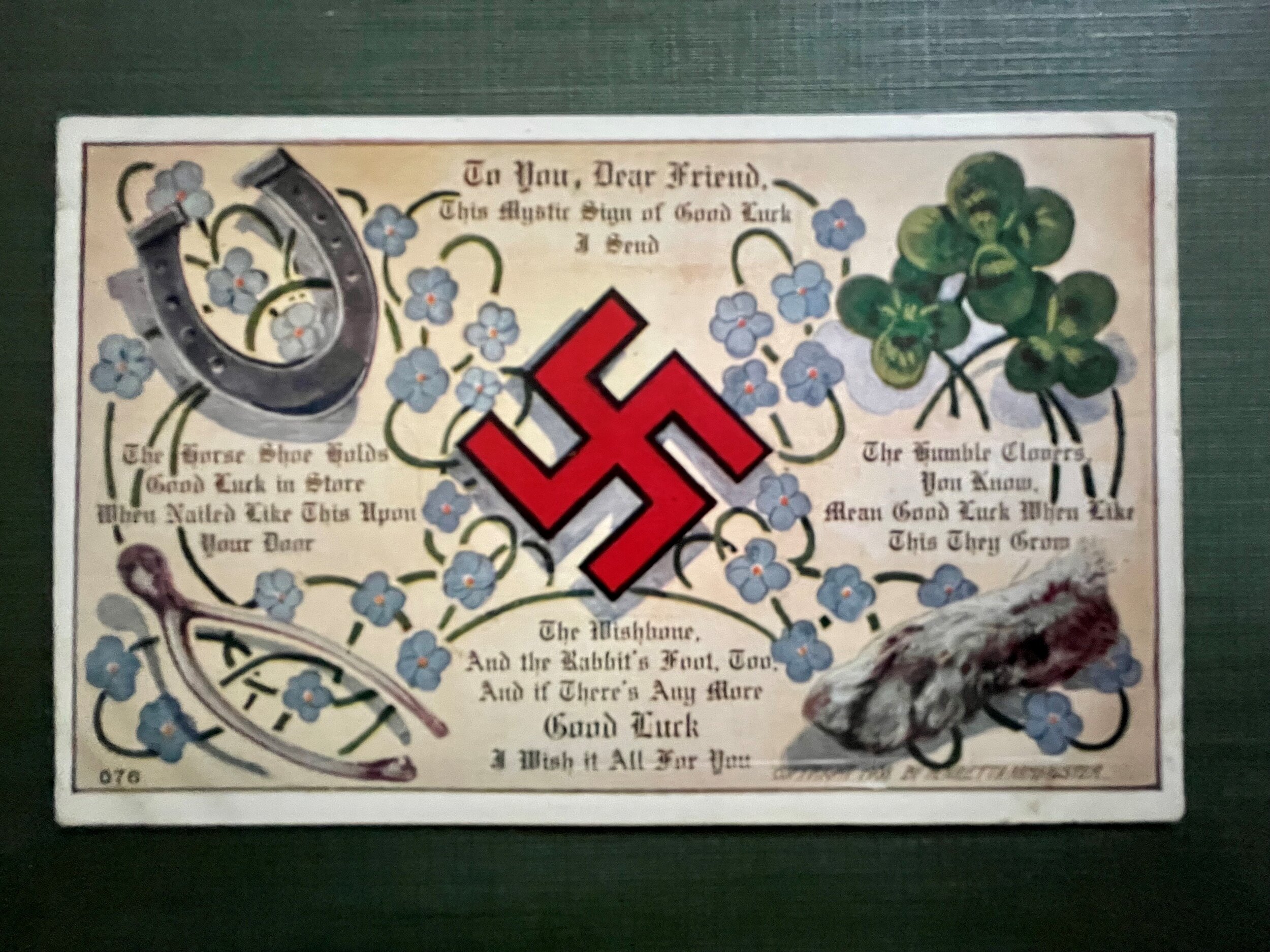

Below is a gallery of examples of use of the swastika as a symbol of good luck and good fortune.

The swastika is an ancient symbol of good luck in Russian culture.

Swastika Jewelry, New York Public Library Digital Collection

A grotesque god presides at a table covered with a cloth printed with the omote manji, a figure resembling a reversed swastika, symbolising infinite mercy

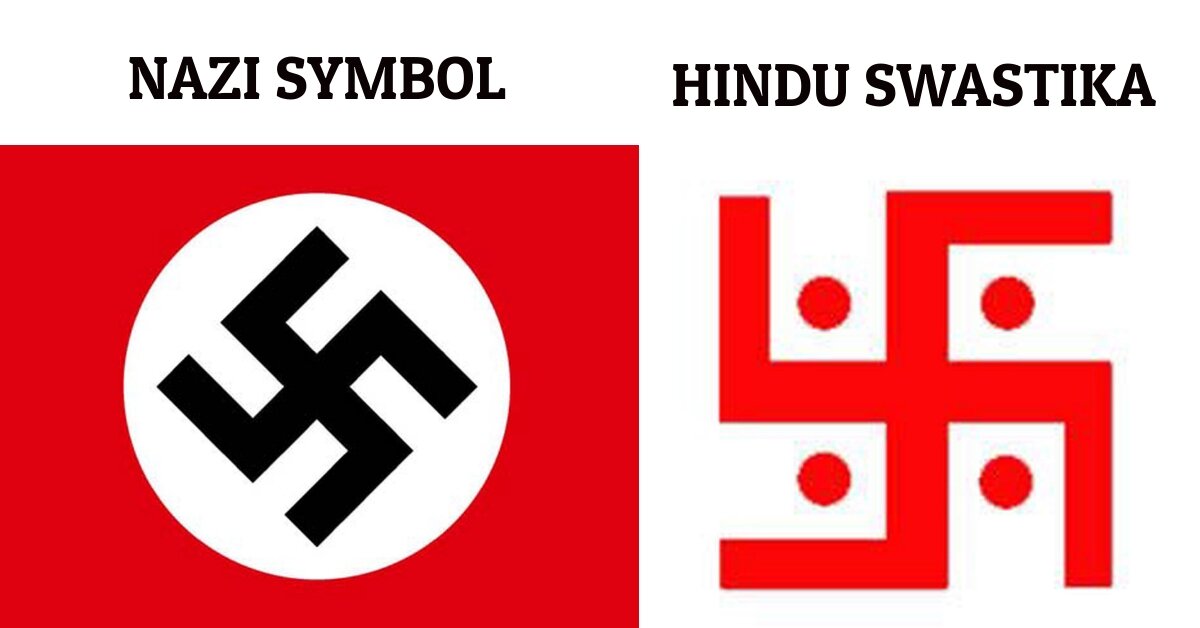

Yellowhead, 1920, from the Wellcome Collection.

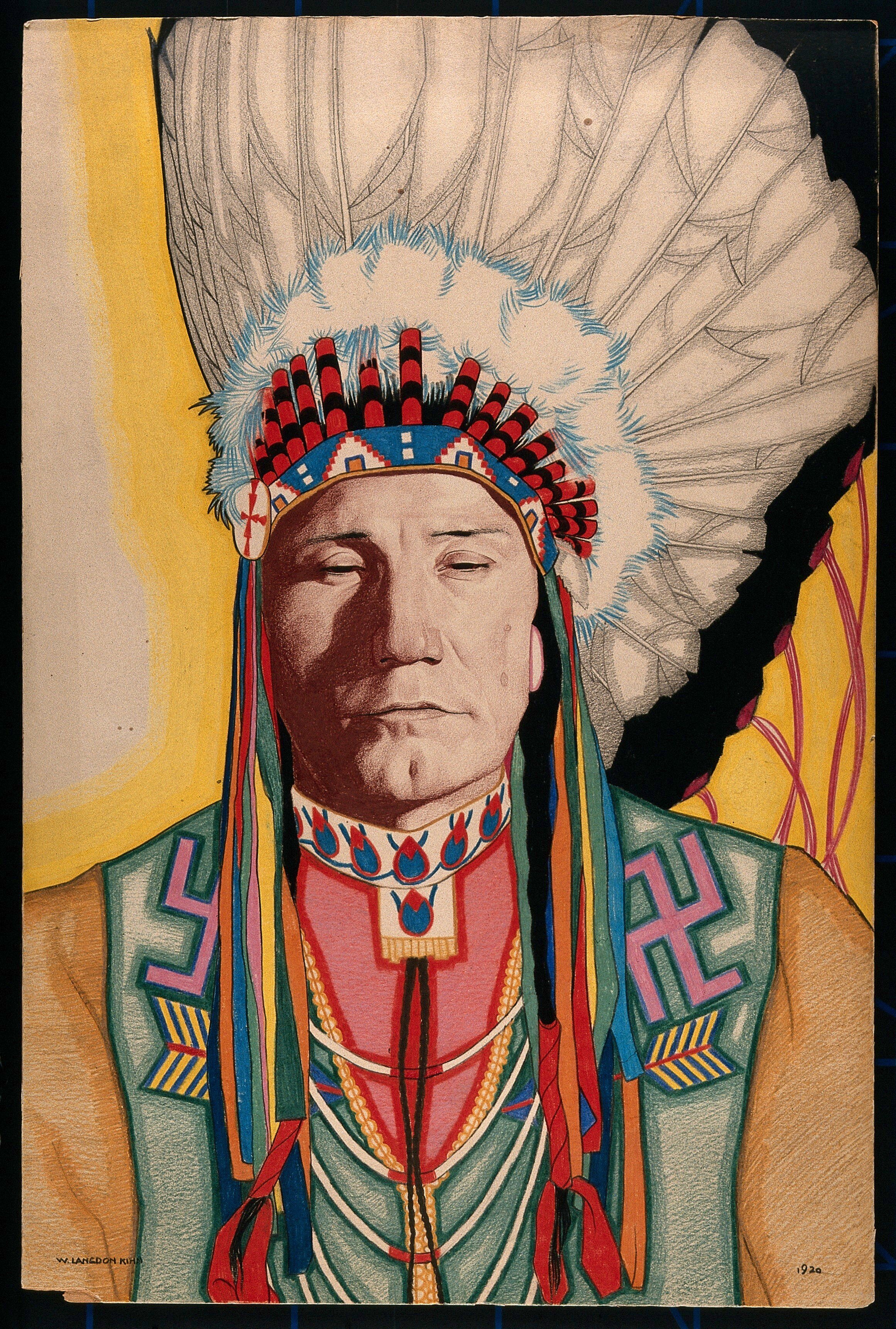

Wills's Cigarettes Card: Swastika

Wills's Cigarettes (reverse)

Postcard depicting swastikas and horseshoe as symbols of good luck, House of Good Fortune Collection.

Postcard depicting swastikas and other symbols of good luck, House of Good Fortune Collection.

Leather postcard "Good Luck Swastika," House of Good Fortune Collection.

Description of the meaning of a swastika from N.M. postcard, House of Good Fortune collection.

Swastika postcard, House of Good Fortune collection.

Tobacco felt with swastika motif, House of Good Fortune Collection

Pre-Nazi Era Swastika; in situ; Copenhagen, Denmark.