Mami Wata

Water Spirit, Snake Charmer or Mermaid?

Mami Wata is venerated throughout Africa and the African diaspora as a being of great spiritual power who is associated with health, wealth, love, and good fortune. She can be beneficent or malevolent — depending on the obedience of her followers. She can shower them with good luck or drown them for insolence.

Her name is a derivation of “Mother Water,” but her origins are not entirely aquatic. According to the Smithsonian Institute:

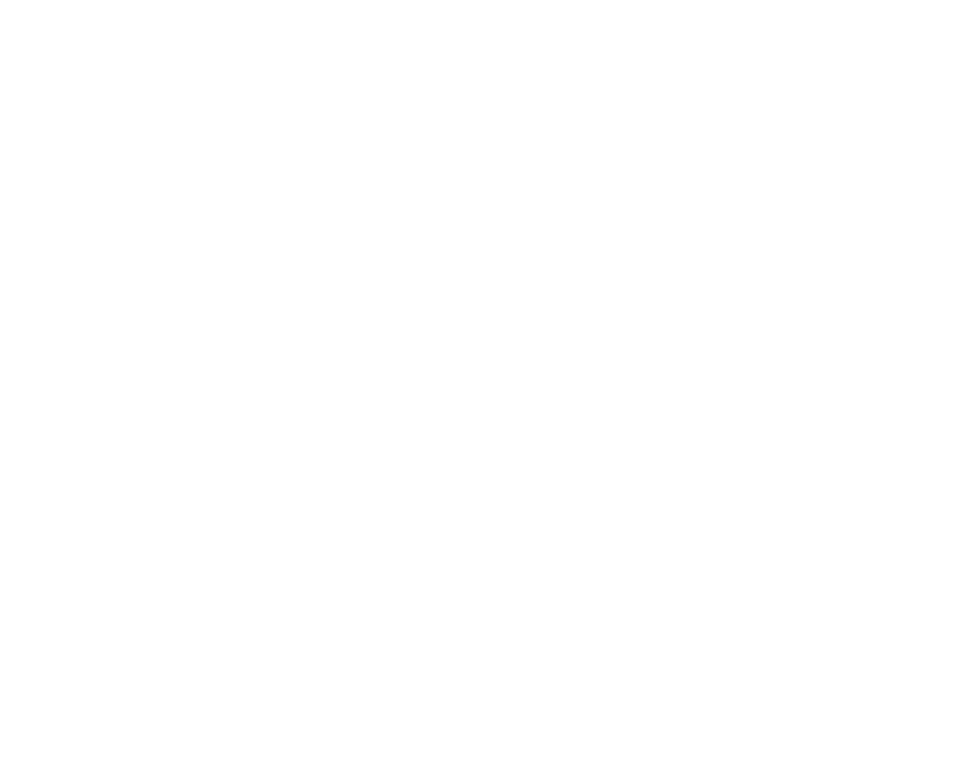

“Her origins can be traced to a late-19th-century German lithograph of a female snake charmer, which appeared in an Indian calendar that circulated widely in western and central Africa. Interested Africans scrutinized the snake charmer's image and invested it with new meaning and a new identity: Mami Wata. They linked her great beauty and foreignness to powers that could provide them protection and wealth in an increasingly precarious world.”

Many African water spirits were depicted as snakes, which may explain why and how this image of a female snake charmer was interpreted as a water spirit. Once this new identity had been established, African sailors carried it with them and spread it far and wide.

Poster of Maladamatjaute by the Adolph Friedlander Company. Note the discrepancy in the captions of these two images.

Handmade figure of Mami Wata, based on German lithograph, House of Good Fortune Collection.

Mami Wata’s power is explicitly commercial. A 2009 Smithsonian Magazine article explains that she is considered “a ‘capitalist’ deity because she can bring good (or bad) fortune in the form of money. This relationship between currency and water makes sense. Her persona developed between the 15th and 20th centuries, as Africa became more present in global trade. The fact that the name Mami Wata is in pidgin English, the language used to facilitate this trade, shows the influence on foreign cultures on the spirit's image and identity.”

She is also quite transactional. The Minneapolis Institute of Art describes her as “[s]treet-wise and fashion-forward, she’ll share the secrets of her success with anyone looking to get a stylish leg up in the modern world and willing to pay her price: gifts and more, sometimes even celibacy.”

Mami Wata figure, National Museum of African Art

In southeast Nigeria among the Anang Ibibio, figures and masks of Mami Wata blended with ideas of earlier water spirits and deities. She was considered a giver of wealth and was also linked with curing problems of infertility. Her brightly painted images often include long fiber tresses.

Mami Wata “Becomes” a Mermaid

What is it about mermaids? This idea of hybrid fish-women who live in the sea has captivated humans for thousands of years.

The House previously explored this question in the context of the “Sirena” charm from Spain, and now we see the mermaid form emerge again in Mami Wata.

So how did Mami Wata “become” a mermaid? The short answer is “through cultural exchange.”

The original German lithograph of the female snake charmer left her lower torso to the viewer’s imagination. She could have had legs or flippers or a mermaid’s tail. (Except, if you look at the inset on the lower right, you can clearly discern the figure of a woman with legs.)

According to the American Museum of Natural History: “Hundreds of years ago, numerous water spirits were said to live in West Africa. In stories told by the Igbo people and others, some water spirits were half-fish, half-human, but many looked like snakes or crocodiles. In the 1500s, ships with statues of mermaids on their prows began arriving from Europe. These strangers came from the sea, like the Africans' water spirits. Could the mermaids on these ships be carvings of water spirits?

“Over time, the European mermaid legend blended with local stories, and more and more Africans came to portray their water spirits as half-woman, half-fish. Many of these stories merged into one, so the most powerful water spirit in many African countries is now known as Mami Wata.”

In Haiti and other parts of the Caribbean, the water spirit Lasirn is part of the Vodou tradition, where followers appeal to her for good luck with work, health, money, and love. She is typically shown with a mermaid’s tail, along with a mirror and a comb for brushing her long, luxurious hair.

The American Museum of Natural History explains that “Lasirn's underwater world is known as ‘the back of the mirror,’ and her mirror is a symbol of the boundary between the two worlds. Followers of Lasirn say she takes them below the water to her world, and they return with new powers. Some women become Vodou priestesses this way.”

Below are some drawings of mermaids from the early 19th century and depictions of Lasirn from Vodou Flags.

Credit: A mermaid, situated on a rock. Etching by J. Godby, 1814, after L. Gahagan. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Three mermaids, one of them showing posterior and front view. Coloured engraving, 1817. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Mermaid with a Pink Comb by M Delice. Voodoo Flag. Haiti. Galerie Bonheur. For information on this piece contact info@galeriebonheur.com or 314.409.6057

Wait…so Black mermaids are “for real”?

Remember back in 2019, when Disney cast Halle Bailey as Ariel in a remake of The Little Mermaid? Remember how some people lost their minds because The Little Mermaid was written by Hans Christian Anderson and therefore Ariel must have been a Caucasian mermaid? The backlash spawned the hashtag #notmyariel along with a lot of arguing about the races of fictional characters. Disney even weighed in on the controversy. And some were quick to point out that Disney already had depicted a black mermaid in the cartoon version of The Little Mermaid that ran in the mid-1990s.

But isn’t everyone who engaged in this debate missing a huge and obvious point that The House’s dear readers know by now???

Just look at the photos on this page and you will see that images of Black mermaids have been around for hundreds of years — yet to The House’s knowledge, Mami Wata, Lasirn and the long tradition of African water spirits were not even mentioned. What a shame.

So the bottom line is that, yes, images and legends of Black mermaids have been for a very long time and people need to get over themselves.

An Aside: Is Madison, the mermaid from Splash, connected to Mami Wata?

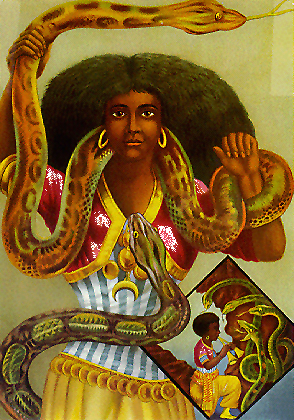

In January 2020, The House had the good fortune to visit “Baptized by Beefcake: The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana” at New York City’s Poster House .

The exhibit focused primarily on 1980s and 1990s films that were shown in local Ghanian “movie theaters” (i.e. a TV with VCR) and advertised with hand-painted signage created by local artists.

One poster in the exhibit was from Splash, starring Tom Hanks and Darryl Hannah as his mermaid love interest. Splash is one of the few American comedies that found success in Ghana, primarily because the female lead character is a mermaid, which connects her to Mami Wata.

Unlike any of the other posters in the exhibit, Darryl Hannah’s face has been almost entirely worn away from passersby touching it in veneration. (!)

Movie Poster for “Splash,” Ghana, photo from Baptized by Beefcake at Poster House, New York City, January 2020.

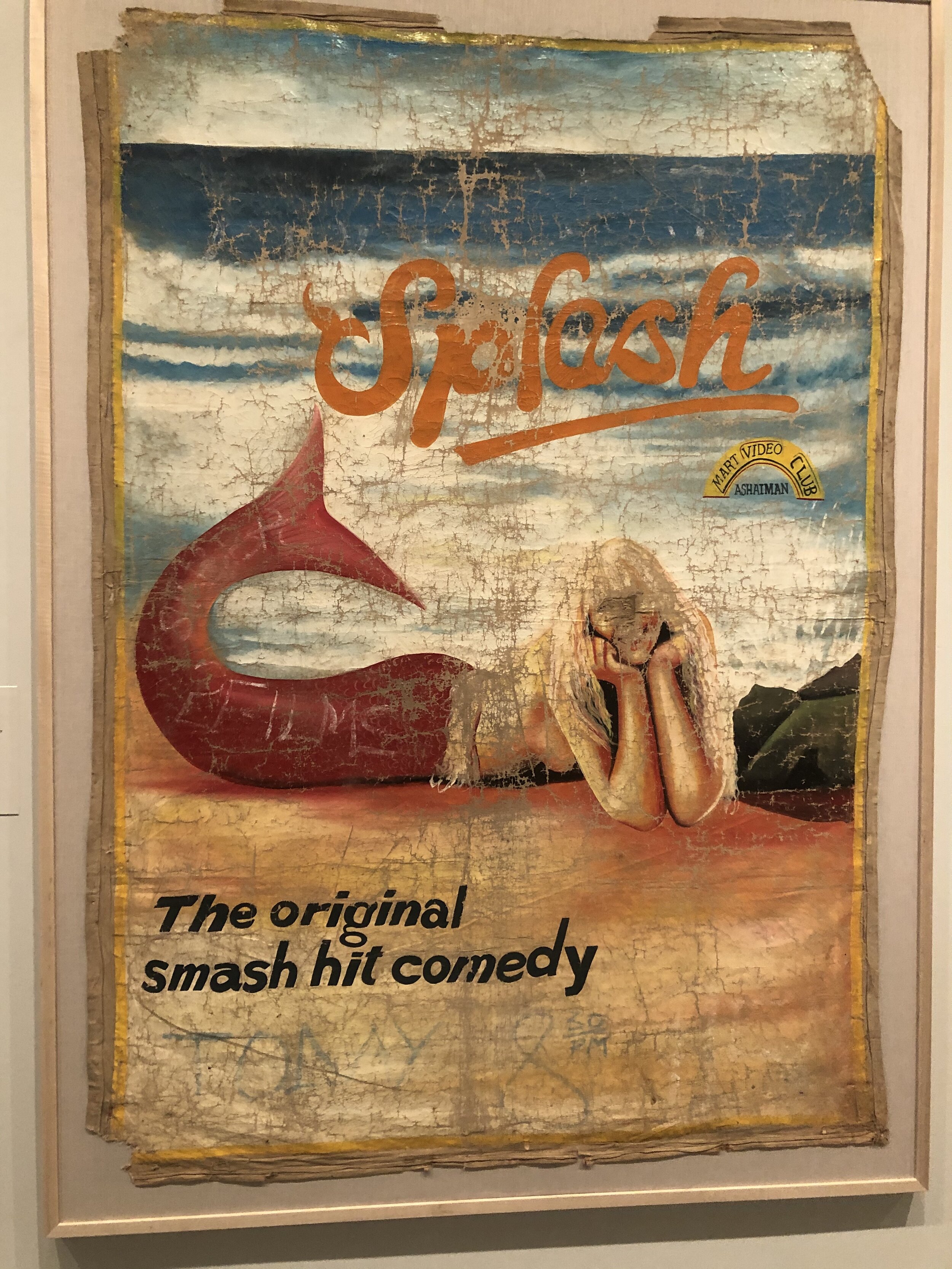

“Justice Money,” African Folk Painted Cinema Poster, Ghana by Mr. Brew, House of Good Fortune Collection. (Note the connection between a female hybrid snake-woman and wealth.)

And below are two beautiful images of snake charmers, just because.